Murder on Federal Street: The tragic tale of Tyrone Everett

BY THE time J Russell Peltz, all of twenty-two years on a beanpole body, strode into the workplace of the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission in September 1969 to select up his newly minted promoter’s license, boxing in Philadelphia was on the downturn, if not in a full-blown decline.

Gone had been beloved attracts akin to Joey Giardello and light-heavyweight Harold Johnson, each of whom received titles. As the ’60s drew to an in depth, even the last decade’s most noteworthy and common fighters in Bennie Brisco and Stanley “Kitten” Hayward had been beginning to fade from relevance. (The lone vibrant spot was the emergence of heavyweight Joe Frazier.) This malaise prolonged past the fighters and their handlers and seeped into the patron base, casting a cynical pall over its eyes. Even Briscoe, the crowd-friendly brawler, was starting to sense that he had outstayed his welcome—in his personal hometown, no much less.

“It’s hard for me to understand, but I get a better reception in New York than I do here,” Briscoe informed the Philadelphia Daily News in 1969. “I’m much more common in Puerto Rico. Jimmy Iselin (his supervisor) needed me to struggle out of New York, however I simply can’t make myself do

that. All my buddies are right here. This is my house. I don’t wish to be a New York City fighter, or a Rhinebeck, N.Y. fighter. I’m from Philadelphia.”

Incredibly, the Philadelphia followers went as far as to bathe Briscoe with jeers.

“I don’t know why they boo,” continued Briscoe. “Maybe the people here like boxers, and that’s one thing I definitely am not. I hit anything I can see … If they’d rather see a guy dance around and then hold, that’s their choice. Let ’em boo.”

Briscoe, of course, was not the primary to get the chilly shoulder from the “City of Brotherly Love.” After he had blown out Floyd Patterson in a single spherical at Comiskey Park in Chicago in 1962 to grow to be the brand new world heavyweight champion, Sonny Liston, who had at the moment made Philadelphia his adopted hometown, anticipated, or at the least hoped for, a homecoming reception that befitted his accomplishment: a key to town, a photograph op with Mayor James H. Tate, the gaggle of followers and press, the entire megillah, quick of a ticker-tape parade. But the second he descended onto the runway at Philadelphia International Airport, Liston was greeted solely with the picture of an airline crew going about their workaday duties. This humiliating episode would immediate Liston to maneuver to Denver, however not earlier than dropping one of his extra notorious strains: “I’d rather be a lamppost in Denver than mayor of Philadelphia.”

It was tanking season in Philadelphia. In 1969, veteran sports activities journalist Tom Cushman, writing for the Philadelphia Daily News, determined to pen a three-part collection inspecting the crumbling state of prizefighting within the metropolis. Cushman solicited the opinion of Herman Taylor, the grand-père of Philadelphia boxing who had been selling exhibits since 1912. Taylor, suffice it to say, was not optimistic.

“We used to have a half-dozen clubs in Philadelphia, and we don’t have anymore,” groused Taylor. “So the young boxer has to try and learn his trade fighting prelims on what cards we can put together. The opportunities aren’t very many. Oh, there are a lot of boxers around, if you want to call them that. But most of them are of a very, very, very poor grade. And I, for one, refuse to run a show just for the sake of having a show. I do not believe in staging lopsided matches. I don’t want the customers walking away disappointed.”

The infrastructure of small membership boxing was falling aside; the expertise, neglected, was withering away. And all Taylor, eighty-two years outdated and ensconced on the second ground of a prim workplace that sat proper above the marquee of the Shubert Theatre (now the Merriam), surrounded by his secretary, matchmaker, and a gallery of classic images of the championship fights that he as soon as promoted—all Taylor may assume of doing was to supply up a number of Hail Marys. “You see, it has come to this point,” he mentioned. “With everything that has happened to boxing, we’re desperate for talent… even enough to keep us going along like we are. And then along, that he falls into the right hands. We can’t afford to lose even one anymore.”

“It is a sad thing,” Taylor added. “I can’t think of a half-dozen young fighters who have excited me in the last two or three years. I don’t really think that boxing will ever die completely. But we have to face it. We’ll never again have the activity we had in the years gone by.”

The prognosis Taylor had charted out was largely on the dot. The annus mirabilis of 1952 was by no means coming again to Philadelphia. Underscoring his pessimism was the truth that there was not a single membership present between May 19 and September 30 in 1969. Jaded managers and myopic promoters nonetheless dominated the land. But Taylor could be confirmed mistaken, to an extent. Less than two months after Taylor caviled to the Daily News, Philadelphia boxing could be put on the trail to its subsequent increase in a manner the octogenarian by no means believed was potential. And Taylor, together with the opposite hard-crusted curmudgeons of the reigning gerontocracy, would have a self-described good little Jewish boy from the Main Line to thank for that.

“There were no real promoters there at the time,” recalled Frank Gelb, a boxing supervisor and shut collaborator with Peltz. “The few good promoters that that they had—they had been falling off a bit. It’s very attention-grabbing as a result of of what boxing was. If you took away Madison Square Garden, there was not a lot boxing on the East Coast, apart from small golf equipment that small promoters would run.

“Russell was the savior. He really was. He made the growth what it was. But the city was ready for it then. They had a big history when boxing was really on its top shelf of having the best boxers of all time. They had many gyms. Russell came to it at the right time, at the right place, and he’d rather see a boxing match than anything in his lifetime. So he fit in perfectly. If it wasn’t for him they never would have reached where Philadelphia wound up in boxing with the greatest fighters of all because if you take a look at the history of it, when Russell got into it, he was the only one that was willing to take the risk and he shared the rewards for it.”

“Russell was an enthusiastic and great promoter and at the same time he had this great talent that was just laying there,” mentioned Don Majeski, a longtime struggle agent and shut

good friend of Peltz. “You had Everett, Briscoe, Monroe, and Hart, Ritchie Kates, all these guys came up at the same period of time. The irony was that Frazier was the Philly boxer, but he rarely boxed there. So you had these middleweights that just clicked. Also, Perry Abner, Sammy Goss, Augie Pantellas. that people wanted to see … The money was coming from the live gate, so you had to go where the money was. Then television came around and you could basically fight guys that were inferior so long as the television networks were willing to buy it. That was the last great era of the live gate. Synonymous with that, you had New York and Los Angeles, with George Parnassus. All of this was just a renaissance for boxing.”

If Peltz had all of the qualities that made up a superb promoter—enterprising, industrious, and enthusiastic—he was not at all times beloved by his fighters. He had a status as a penny pincher and was notoriously stingy with comp tickets. At the identical time, nobody else in Philadelphia was placing up his personal cash to stage fights and giving fighters a possibility to ply their commerce. And the fighters, regardless of what number of occasions they cursed Peltz beneath their breath, understood this.

“There were no fights happening then,” mentioned Mike Rossman, the sunshine heavyweight champion who usually fought for Peltz. “Russell kept boxing alive in Philadelphia. He don’t like to pay. But he still kept boxing alive. It’s the truth. He was the only guy doing it, and that’s who you go with.”

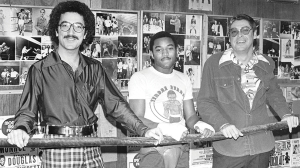

Promoter J Russell Peltz, Tyrone Everett, and his supervisor Frank Gelb (Peltz Boxing Promotions)

Scranton, Pennsylvania. October 30, 1971

It was a Tuesday evening and Frank Gelb and his spouse Elaine had been ringside on the Catholic Youth Center, the place they joined greater than 3,200 paying clients to observe Bob Foster, the highest mild heavyweight of his technology, defend his world title towards Tommy Hicks. Gelb, a resident of close by Norristown and proprietor of a furnishings retailer, had a significant hand in organizing the cardboard. The until whizzed all evening, producing a gate of greater than $25,000, no chump change in these days. The primary occasion itself didn’t change into a lot of a contest—Hicks was stopped within the eighth spherical—nevertheless it was a giant evening, nonetheless, as large because it bought sporting-wise within the hardscrabble city of Scranton. It would take a number of years earlier than Gelb could be ready to surrender his day job as a furnishings seller, however, within the meantime, right here he was, in Scranton, of all locations, moonlighting, like his newly revived pal Hurricane Roberts, a fighter-turned-police officer, within the boxing enterprise.

Before it turned often called the setting for the popular culture phenomenon of [i]The Office[i] or the birthplace of Joe Biden, Scranton was related primarily with 4 issues: coal, iron, metal, and locomotives. By the Seventies, very like what occurred to Philadelphia, Scranton’s industrial base—its anthracite financial identification—was slowly, however absolutely, coming aside, mirroring the nation-wide, post-World War II course of of deindustrialization that Detroit, Cleveland, and scores of different once-proud blue-collar cities throughout the rising Rust Belt. Nevertheless, it was in Scranton that Gelb shaped one of the bases of his nascent boxing operations.

Despite Gelb’s serendipitous begin, there was nothing slipshod or dilettantish about his new endeavor; he had actual designs, hopes that went past being simply the handler of a Norristown patrolman. “An avocation quickly became a vocation,” Gelb later mentioned. One of the primary issues he did was construct relationships with native powerbrokers. From the administration duo of William “Pinny” Schafer and Pat Duffy, longtime fixtures on the Philadelphia boxing scene finest recognized for dealing with the careers of Leotis Martin, Bennie Briscoe, and “Boogaloo” Watts amongst others, Gelb acquired a half-dozen fighters to kind the core of his early secure. (A couple of years later, Gelb would buy Matthew Saad Muhammad’s contract from the identical tandem.) In Scranton, Gelb paired up with native promoter Paul Ruddy to place on month-to-month struggle playing cards on the Catholic Youth Center, a 4,000-seat area that served as one of the first athletic venues within the metropolis.

For a number of years, Gelb and Ruddy had been virtually the one sport on the town, selling most of the boxing exhibits in northeastern Pennsylvania. It was, by most measures, a profitable partnership, aided no much less by the passion of the residents of Lackawanna County. As far as skilled sports activities went, boxing was essentially the most outstanding attraction to hit Scranton, with the exception of faculty soccer.

“When we did a fight there, it was a huge operation,” Gelb recalled. “It was like a New Year’s Eve party most of the time. Because people would go out to all the restaurants and eat before and go to the bars afterward and drink. They looked forward to boxing, and it was the biggest thing that happened for the city of Scranton at the time. Boxing was probably the most professional sport they had on a regular basis. We did that for many years. I was promoting, I was managing, I was handling a lot of boxers from that area that I tried to take to bigger heights.”

One of these boxers was Ray Hall, a extremely regarded featherweight prospect from close by Wilkes-Barre. Gelb had slotted Hall right into a four-rounder on the Foster-Hicks undercard. An completed newbie, Hall had already constructed up a reputation for himself in native circles. The considering was that, along with changing into a high contender, he may additionally grow to be a reputable draw down the road. With a 5-0 file, he was on the appropriate monitor.

But Hall was matched powerful in his sixth struggle that Tuesday evening in October 1971, whether or not anybody on his aspect realized it or not. In the opposite nook was a wiry 18-year-old Black child carrying pigtails from South Philadelphia with a 1-0 file. Unlike Hall, Tyrone Everett flew largely beneath the radar as an newbie. Nothing was extra indicative of his marginal standing than the truth that native newspaper studies main as much as and after the struggle referred to him as “Tyrone Edwards.” Hall, for his half, was not beneath the identical false impression, for it was Everett who had handed him his final loss as an newbie. By selecting to face him once more, Hall and his mind belief clearly didn’t view Everett as a lot of a risk. Perhaps they had been satisfied that Hall’s aggressive type would produce higher leads to the professional ranks. Stylistically, Everett was the entire antithesis to Hall and his headlong method. But there was a less complicated rationalization for Hall’s optimism in a second go-around.

One month earlier than, on September 25, Everett made his skilled debut towards fellow debutant Neil Hagel on the CYC on a card that had additionally featured Hall. In a four-round bout, Everett received a call towards Hagel—albeit controversially. While it was an in depth struggle, most ringside observers believed Hagel had performed sufficient to deserve the win, with one native newspaper describing how “heavy body blows had Everett reeling around the padded circle.” The paper added, bluntly, that “Neil Hagel appeared to have been robbed of the decision in his debut as a prize-fighter.”

So Hall was feeling bullish for all the appropriate causes. But Everett, unhealthy debut however, had good motive to really feel assured in himself as nicely. Everett knew that two weeks earlier, in Philadelphia, Hall had picked up a comparatively simple determination, however not with out leaving with a big minimize over his left eye, the consequence of a headbutt. Two weeks later, that gash was nonetheless tender, a undeniable fact that didn’t escape the guileful Everett. With the main target of an osprey scanning for trout, Everett made it some extent to focus on the wound from the opening bell. As he would later say, “You look at a man’s face to see if he’s been cut. You check if there’s a lot of scar tissue. I always look at the eyebrows.” Before lengthy, blood started drizzling down Hall’s face from the identical sore spot. The struggle was resembling a beatdown.

Meanwhile, Gelb was wanting on despondently, his coronary heart in his throat, like one of these poor Las Vegas souls witnessing their life financial savings dry up on the slot machine. At one level, Gelb’s spouse Elaine turned to her blanched husband and cracked, “I think you’re backing the wrong fighter.” It was a shutout; Everett received each spherical on the scorecards. Gelb might have been a boxing neophyte, however he may sniff out a enterprise alternative as adroitly as a bloodhound sniffs for contraband. Heeding his spouse’s recommendation, Gelb moseyed as much as the victor after the bout and floated the concept of working collectively. They struck a deal shortly thereafter. “Ray Hall was good, I mean real good,” Gelb as soon as informed the Philadelphia Tribune. “I had visions of a championship fight(er). Everett … destroyed my fighter. I couldn’t believe it.”

When Gelb later spoke to Peltz, he gushed about his new signee and prodded the fledgling promoter to come back to Everett’s subsequent struggle to see for himself. The subsequent struggle could be on March 7, 1972, once more in Scranton.

“So I went to the show and that was the night that Ray Hart—not to get confused with Ray Hall, and no relation to Cyclone Hart or any of the other Harts—was fighting Everett,” Peltz recalled. “Ray Hart was a Joe Frazier with speed, and he came right after Everett. I mean Ray Hart really jumped on his ass. And he was a decent prospect at the time, Ray Hart, and he made Everett look like Sugar Ray Robinson. I saw that that night… and when the fight was over I ran over to Gelb, and I said, ‘Let’s make a deal right here.’ And then [Tyrone] fought for me exclusively. That night? Whew, he was good.”

Of all of the fighters to emerge from the Philadelphia renaissance of the Seventies, a sizzling crucible of competitors that solely waned with the emergence of Atlantic City as a vacation spot for marquee boxing, none was as proficient as Tyrone Everett. There had been others, for positive, who had been extra thrilling contained in the ring, others who had been extra accessible, and since they had been extra accessible, extra beloved: Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, Willie “The Worm” Monroe, Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, Billy “Dynamite” Douglas, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, Matthew Saad Muhammad, and, of course, the doyen, “Bad” Bennie Briscoe, the hard-nosed slugger usually considered the quintessence of the Philadelphia boxing spirit.

As light-heavyweight champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, who dropped a call to Briscoe early on in his profession, as soon as informed The Ring, “When you say Philadelphia, you right away think of Bennie Briscoe. No nonsense, blue-collar worker. Bennie was the greatest fighter to never win a world title.” The Briscoe Awards, the annual ceremony celebrating Philadelphia fighters previous and current, are named after him because of this. Unlike Everett, their names have continued to flow into at the moment within the creativeness of the boxing public. None of them ever received a title and some of them, like Monroe, by no means acquired a title shot, however they however helped reinvent Philadelphia because the premier struggle capital on the East Coast for a quick however bountiful spell.

And all of them, crucially, fought as middleweights––a major truth since virtually all of them, at one level or one other, confronted the dominant middleweight of that period, Marvelous Marvin Hagler, who, from 1976 to 1978, made the lengthy trek down from his house in Brockton, Massachusetts, to Philadelphia 5 occasions to face town’s high brass, going 3-2, dropping selections to Monroe and Watts, each of whom he would later cease in rematches. Part of the rationale why these Philadelphia middleweights have been assured a significant afterlife may be attributed to Hagler’s enduring legacy.

That Everett was a diminutive fighter—he was a pure featherweight who discovered himself competing at junior light-weight for many of his profession as a result of of a dearth of alternatives on the lighter weight—was however one characteristic that distinguished him from the native orthodoxy. Where he stood out much more was in temperament and sensibility. With his smoldering beauty, his wind-flapping pigtails, and a swagger bordering on insolence, Everett assumed a mode that was stridently against the extra rugged, workmanlike method of his friends and predecessors. “Wily” and “cunning,” in spite of everything, weren’t phrases usually ascribed to the native fighters by the opposite,” Everett was all silken polish and floor perfection. Stick and transfer, counter. Hit and never be hit. Critics known as it hotdogging, boring, a time suck. For Everett, it was merely good boxing. It was boxing, furthermore, that preserved his face, which he at all times handled like a Romanov Fabergé egg.

His brilliance was additionally a supply of repeated frustration. For all his technical astuteness, sangfroid, and whippet quickness, for all his skill to hit all the appropriate notes contained in the cordoned-off boundaries of a boxing ring, Everett not often rose to that pitch of ardour that exemplifies the prime attraction of a blood sport, that unhinged fervor which constituted nothing lower than a pure state of being for fighters akin to Roberto Duran and Aaron Pryor. His heavy reliance on finesse was usually confused by his detractors as an indication of weak point. In truth, there was nothing in his background to recommend that he was any much less resilient than the likes of Bennie Briscoe or Matthew Saad Muhammad. It is a truism that solely the poorest and most marginalised in society find yourself selecting boxing as a pursuit, and, on this, Everett was no exception. His origins had been as hardscrabble and harrowing as any of his extra beloved friends.

Source link